The last year and a half has been particularly demanding from the business point of view. In fact, the project on which I worked on has seen a couple of big organizational changes that required also a change in the way the codebase was managed.

Today I’d like to share this experience with a particular focus on the branching strategy.

Intro

Git

Git has become the de facto standard for version control systems in the software industry. Git is a simple mechanism with few critical concepts:

- blob: a binary representation of a file

- tree: the binary representation of a folder. It’s another binary file containing references to other blobs and trees

- commit: a snapshot of the state of the files in a repository, in a given instant

What really makes commits valuable is their relationships to other commits. Those relationships generate the notion of history and revision.

Branching strategy

A branch is nothing but a reference to a commit. Their creation and merge are really simple. Thus, branches can rapidly get out of hand. In this scenario, branching strategies come into play.

These strategies are rules developers decide to adopt on:

- When a developer should branch

- From which branch they should branch off

- When they should merge back

- And to which branch should they merge back

The Divine Comedy: branching edition

There’s an abundance of different strategies, each with its own pros and cons (git flow, GitHub flow, trunk based development, …). What I want is to describe my journey between the different strategies we adopted, and talking about journeys…

I’ve identified three phases that, in my head, automatically associate with the three parts forming Dante’s “Divine Comedy”. Let’s jump in the first phase.

Phase 1 - Purgatory

In the initial phase of the project, many teams were working on a single codebase. We didn’t have a production environment but only a development environment used to test backend and frontend integrations.

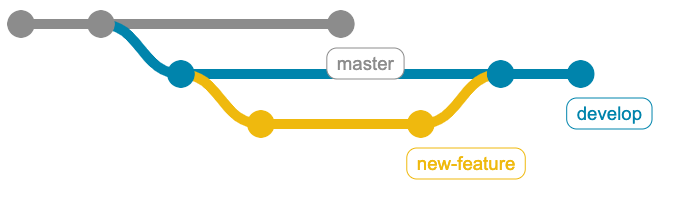

Business gave requirements on new features that were released in that development environment. Our branching strategy was:

- a single development branch (named develop) - master was in place but not actively used

- new features developed on branches created from develop

Really straight-forward, but effective. In fact, I’ve associated it to the purgatory: on one hand the lack of strict rules make the process really smooth, on the other hand there was no uniformity between teams.

Phase 2 - Paradise

We soon realized that the previous model had a lot of limitations. The need of having a unique vision over the product brought to the creation of one big team working on the same codebase.

We made the maximum effort: business gave requirements continuously. We also put in place different environments: test, stage and production.

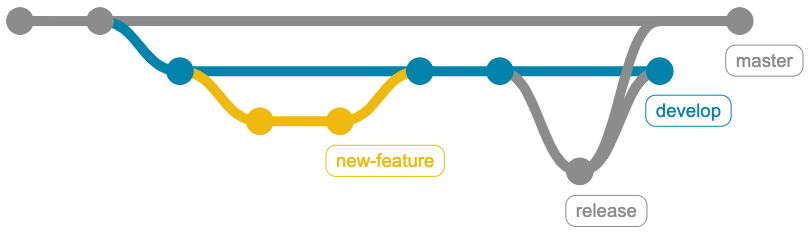

To better support this change we adopted a strategy really similar to a standard git flow:

- develop is the development branch

- master contains production code

- feature branches to develop new features

- release branches to identify release candidates

Maybe not the true paradise, but we were almost there. Well defined rules allowed developers to concentrate on the development. We were also supported by robust CI/CD processes.

Phase 3 - Hell

During the final stage of the project the way business people gave requirements changed.

The main problem was that different requirements had to go into production with different timings, even if they had to be developed at the same time.

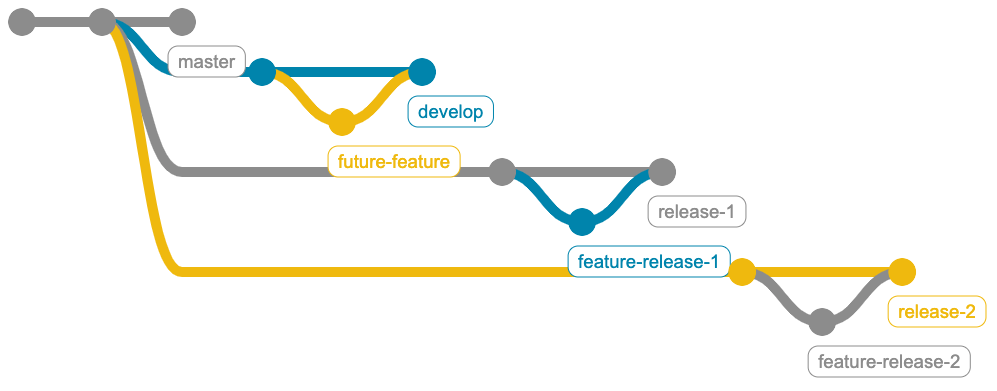

Thus, the branching model changed a lot. It’s something like the Release Train model Martin Fowler explained here:

- release/DD_MM_YYYY is the branch in which features to be released on date DD_MM_YYYY are developed. We can have many of them at the same time

- develop is used for future functionalities (that is, features outside the planned releases)

The strategy is crystal clear, but completely different with respect to the previous one. And that’s why this is the hell for developers: errors and misunderstandings are really likely to happen. It takes time to take all the developers on the same page. CI/CD and environments changed as well.

Conclusions - back to Paradise?

That’s the end of my journey. Probably, there will be another stage in which we will proceed splitting the monolith into micro services. Teams organization will change as well to compose the so called feature teams. This will improve flows and will resolve a lot of the problem we had. But this is another story…

What I learned is that business choices impact significantly technical matters. Thus, all the kind of changes I described in the article should be considered carefully and should not happen so often. Not only as a matter of costs, but also to avoid developers headaches.